Clinical, social, and economic burdens

Clinical burden

Increased complications and

hospitalizations1

In a single-center study of 98 patients with rCDI,

most patients (82/98) with recurrence had a

CDI-related hospitalization within 12 months1,a

Social burden

Negative impact on quality of life3,4

Patients with rCDI reported decreased QoL across

measures relating to physical, emotional, professional,

and financial consequences3,4

~90% of surveyed patients (210/235) with rCDI were

worried about having another recurrence4

Economic burden

Substantial burden on healthcare resource utilization1,5,6

Total all-cause direct medical costs increase with each recurrence 5,b

aData derived from a US study designed to identify the health consequences of rCDI including need for repeat hospitalization, intensive care unit (ICU) stay, and surgery. The study population included 98 patients who developed rCDI (defined as infection that occurred within 56 days after the end of treatment of the original infection).1

bBased on a longitudinal retrospective analysis of real-world data for commercially insured adults from January 2010 to June 2017. All-cause direct medical costs included inpatient, outpatient (physician office visits, outpatient hospital visits, emergency department visits, other outpatient services), and prescription drug costs. Costs have been adjusted to reflect 2023 US dollar amounts.5

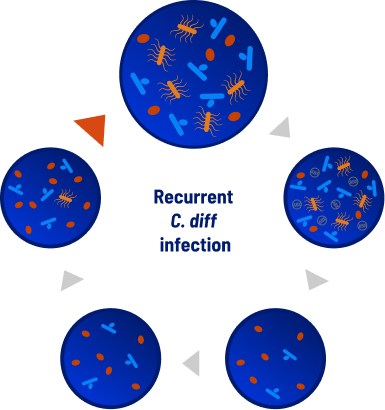

Risk and mortality rates of rCDI escalate with each infection7

Early intervention can be key to minimizing clinical consequences of recurrent C. diff infections.8,9

Toxin-producing C. diff bacteria

Beneficial bacteria

C. diff spores

8.3%

30-day all-cause mortality rate with first recurrence

(n=208/2521)11

National cohort of adult Veterans at a VA facility with

multiple comorbidities from 05/2010 to 12/201411

35%

Recurrent CDI 12-month all-cause mortality rate

(n=53,858/151,596)11

Retrospective cohort study of

Medicare patients aged 65 and older with multiple

comorbidities from 01/2010 to 12/201612

Recurrence usually occurs within 1 to 2 weeks after completing

antibiotic therapy in a window of vulnerability

The risk of a second recurrence of C. diff

infection increases

significantly after the first13,14

Dysbiosis: the antibiotic paradox

Antibiotics are the standard of care, but could leave the patient vulnerable to a recurrent infection. C. diff infections treated with antibiotics can cause dysbiosis, an imbalance in the microbiome characterized by a lack of microbial diversity.16

Dysbiosis creates a window of vulnerability that could lead to rCDI7,8,9,16

Microbiome Key

Toxin-producing C. diff bacteria

C. diff spores

Beneficial bacteria

C. diff-specific antibiotics

Toxin-producing C. diff bacteria

C. diff spores

Beneficial bacteria

C. diff-specific antibiotics

References: 1. Rodrigues R, Barber GE, Ananthakrishnan AN. A comprehensive study of costs associated with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2017;38(2):196-202. doi:10.1017/ice.2016.246 2. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed October 25, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/2019-ar-threats-report-508.pdf 3. Armstrong EP, Malone DC, Franic DM, Pham SV, Gratie D, Amin A. Patient experiences with Clostridioides difficile infection and its treatment: a systematic literature review. Infect Dis Ther. 2023;12(7):1775-1795. doi:10.1007/s40121-023-00833-x 4. Lurienne L, Bandinelli P-A, Galvain T, Coursel C-A, Oneto C, Feuerstadt P. Perception of quality of life in people experiencing or having experienced a Clostridioides difficile infection: a US population survey. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4(1):14. doi:10.1186/s41687-020-0179-1 5. Feuerstadt P, Stong L, Dahdal DN, Sacks N, Lang K, Nelson WW. Healthcare resource utilization and direct medical costs associated with index and recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection: a real-world data analysis. J Med Econ. 2020;23(6):603-609. doi:10.1080/13696998.2020.1724117 6. US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index (CPI) Inflation Calculator. Accessed November 7, 2025. https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm 7. Feuerstadt P, Theriault N, Tillotson G. The burden of CDI in the United States: a multifactorial challenge. BMC Infect Dis. 2023;23(1):132. doi:10.1186/s12879-023-08096-0 8. Feuerstadt P, Louie TJ, Lashner B, et al. SER-109, an oral microbiome therapy for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(3):220-229. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2106516 9. Jain N, Umar TP, Fahner A-F, Gibietis V. Advancing therapeutics for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections: an overview of Vowst’s FDA approval and implications. Gut Microbes. 2023;15(1):2232137. doi:10.1080/19490976.2023.2232137 10. Song JH, Kim YS. Recurrent Clostridium difficile infection: risk factors, treatment, and prevention. Gut Liver. 2019;13(1):16-24. doi:10.5009/gnl18071 11. Appaneal HJ, Caffrey AR, Beganovic M, Avramovic S, LaPlante KL. Predictors of mortality among a national cohort of veterans with recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2018;5(8):ofy175. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofy175 12.Feuerstadt P, Nelson WW, Drozd EM, et al. Mortality, health care use, and costs of Clostridioides difficile infections in older adults. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2022;23(10):1721-1728.e19. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2022.01.075 13. McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Greenberg RN, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in combination with standard antibiotics for Clostridium difficile disease. JAMA. 1994:271(24):1913-1918. 14. McFarland LV, Elmer GW, Surawicz CM. Breaking the cycle: treatment strategies for 163 cases of recurrent Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(7):1769-1775. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05839.x 15. Fu Y, Luo Y, Grinspan AM. Epidemiology of community-acquired and recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2021;14:17562848211016248. doi:10.1177/17562848211016248 16. Normington C, Chilton CH, Buckley AM. Clostridioides difficile infections; new treatments and future perspectives. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2024;40(1):7-13. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000989 17. McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(7):e1-e48. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1085 18. Dificid. Prescribing information. Merck & Co; 2022. 19. VOWST [Prescribing Information]. Bridgewater, NJ: Aimmune Therapeutics, Inc. 02/2025.